June 27th, 2014

Episode 12: Vaya con Dios

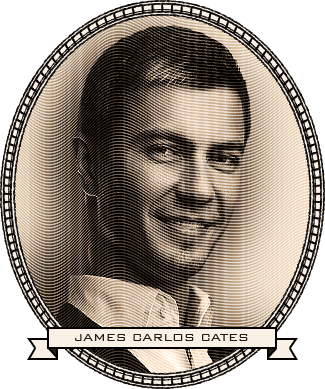

James Carlos Cates flips through a recent edition of South Texas Catholic while he waits for Bishop Muñoz to return from the bathroom.

The magazine, which is published by the Catholic Diocese of Corpus Christi, includes an article about the Helping Hands Beach Restoration Project – an IRS-recognized Public Service Organization founded by Cates and George Boyd.

Despite Cates’ repeated assurances that he read the article when it was published online two months earlier, Bishop Muñoz politely insisted on producing a paper copy for Cates to review and take home with him.

It is Sunday, and Cates spent the weekend with a Helping Hands team who are working along the northern tip of the Padre Island National Seashore. He is exhausted and eager to return home to his family, his business, and his campaign. But he thought it foolish to decline the Bishop’s unexpected invitation to meet.

Bishop Muñoz returns, and Cates slips the magazine inside his bag.

“Pardon me for abandoning you, but I must make more trips to the bathroom than I did as a young man. I see it as another opportunity sent from the Father to help me learn humility,” the Bishop says with a tired smile. “Please, would you join me?”

The Bishop crosses his office and stands before the window. Cates follows him.

Bishop Munõz directs Cates’ attention to a long wall between the diocese offices and the sidewalk along Carancahua Street.

“My predecessor built that wall because tourists and the faithful seeking entrance to the cathedral often mistook our diocese offices for their destination. The confusion was very disruptive to diocese business, I am told. I might have built that wall, too, under the same circumstances.”

There is a long line of tired, haggard people standing outside the wall, advancing slowly. Cates tracks the line to where it ends at a ragged hole cut in the wall.

“That is called the Pilgrim’s Arch, by some,” the Bishop explains, “although it has no official name. No one knows who cut it in the wall, but we know why.”

Cates watches as the people in line – most of them immigrants from Central and South America – take turns crawling through the Pilgrim’s Arch. He waits for the Bishop to explain.

“Six years ago, a 12-year-old Salvadorian boy who was headed to Atlanta to reunite with his mother, died outside the wall, right there where that hole is now. We know from the note in his pocket that he was travelling with his uncle for some part of his journey. But, like so many young people making the pilgrimage to a better life, he must have lost his escort along the way – most likely to greed-fueled law enforcement officials, drug cartel soldiers, or other predators.

“Somehow the boy made it into Texas and all the way to Corpus. We suspect that he was seeking sanctuary in the cathedral, but he must have been overcome with exhaustion after his grueling journey. He sat with his back against the wall – perhaps in an effort to regain his strength — but he never stood up again. He died right there – alone, dirty, hungry, and probably filled with fear.”

Cates feels sick to his stomach, and behind the tears welling in the Bishop’s eyes, Cates can see anger. They stand in silence for several minutes, watching as men, women and children take turns crawling through the arch.

Along the inside of the wall, a few feet from the arch, is a mosaic depicting the six flags that have flown over Texas. Beneath the flags are illustrations of people who made their way into Texas over the last 500 years. At the mosaic’s far left end – before the Spanish flag and a conquistador – there is a depiction of a regal Native American.

“That mosaic was a gift from a parishioner fifteen or twenty years ago,” Bishop Muñoz explains when he regains his composure. “It was placed here, on the far side of the cathedral complex, and all but ignored until the arch was cut after the boy’s death.

“It’s the first thing pilgrims see after they’ve crawled inside the Cathedral complex, and they touch the mosaic in search of blessings. The people say that whoever touches it during a long journey will reach their destination safely.”

Cates tries to imagine under what conditions he would pack up his children and send them thousands of miles northward without his guidance and safekeeping. He shudders when he imagines Larisa receiving the news that their oldest boy died on a grueling trek like that.

“With respect, Bishop,” Cates says apologetically, “why did you invite me here today?”

“I have been following you for some time, Señor Cates. We share a common interest in removing Gustavo Garza’s hand from the Speaker’s gavel.”

Cates is surprised, but his face does not show it.

“The Speaker must grow politically, or he will die politically,” the Bishop continues. “No matter what he and his talking heads say, he wants to run for the U.S. Senate. His political allies, his family, his business partners – they are all preparing for that step.

“But he’s taken an aggressive, hardline stance on immigration in the past, and his position on that issue tells these pilgrims – and their supporters – that the immigrants are engaged in something bad. What the Speaker fails to understand is that the people – and their supporters – are sure that we are engaged in a Godly endeavor to raise them up. Why else would these pilgrims risk their lives, and the lives of their families?

“Despite his recent, deathbed conversion, we know who the Speaker really is. We are a forgiving people, and we counsel forgiveness as Christ’s way, but its hard to act like Christ when the government continues to attack our people. It took a long time for our opinion on this issue to register, but they’re listening now, aren’t they, Señor Cates?”

Cates agrees that Texas politicians are listening now.

“That’s part of what created the opportunity for Independents to affect the system,” the Bishop continues. “While we cannot embrace the new civic religion that is represented by people like you, we welcome and embrace your position on immigration. While the Church should never take an official position on the election of political candidates, there are – among the faithful – allies who will help you.”

“How?” Cates asks. He feels dizzy with the realization that a man representing the powerful Catholic Church seems to be offering his help.

“For now, let me just say this. The Speaker’s brother is a selfish, decadent man. While he tells their friends in the Metroplex that he is on their side in the fight to win the International Law Enforcement Training Center, out the other side of his mouth he is making secret deals in San Antonio. My sources tell me that he has acquired, through intermediaries, a significant parcel of the land on which the training center could be built.”

Cates is troubled by this information. He feels suddenly vulnerable, but he does not want to offend this man-of-God who claims to be offering his help.

“Does that not help you?” the Bishop asks, clearly surprised by Cates discomfort.

“I am grateful for your friendship and support, Bishop. But I need to spend some time digesting everything I saw and learned here today. May we meet again soon to discuss all of this further?”

“You are welcome here anytime, mi hijo. Will you stay for mass? The cathedral is sure to include people whose bellies you helped fill through your Helping Hands project. It might give you a unique perspective to see them celebrating the blessing you helped provide.”

Cates thinks about George Boyd and their bet about how big they could grow their non-profit public service organization. They never considered immigrants when they started, nor do they spend much time thinking about them now. The immigrants who are temporarily employed by the organization are simply a means-to-an-end – cleaning up the coast so that outdoorsmen like Cates and Boyd can continue to enjoy all that the rich Gulf has to offer.

Cates is ready to leave, but he feels compelled to offer a sign that he is grateful for the Bishop’s supporter.

“I must admit to you, Bishop, that I am not a believer.”

“Well,” the wise, old bishop replies gently, “keep watching. Maybe you haven’t seen enough yet.”

Cates smiles. “Thank you, Bishop. I will watch, thank you.”

Bishop Muñoz makes the Sign of the Cross, and the two men shake hands

“Vaya con Dios, Señor Cates.”

“Y usted, Bishop. Gracias.”

Cates walks out of the diocese offices toward the pilgrim’s arch. He stands looking at the mosaic, on which he can see thousands of greasy fingerprints reflected in the sun. When there is a break in the line, Cates drops to his hands and knees and crawls out through the arch.

Comments

COMMENT POLICY

The Independent Candidate is pleased to include your comments and observations about this story. We encourage lively debate on the issues of the day, but we ask that you refrain from using profanity or other offensive speech, engaging in personal attacks or name-calling, or posting advertising. To comment, you must be a registered user of The Independent Candidate, and your user name will be displayed. Thank you for sharing your thoughts. We're here to serve.

You must be logged in to leave a comment.

Login | Register

June 29, 2014

sotxzman

Well done, josh. Your trip to PA must have added a bit of opportunity for a more thoughtful approach to our immigrants passing into and resettling our state. In the rio Grande Valley the nuns in Catholic Charities so bravely stand in the breach to provide a heart to God's unfortunate. To bad we must weigh this as against , with reality, the costs to we taxpayers and legitimate concerns as to jobs , schools, and skirting the legal process of other quotas from other countries and the insurance of certain screening, really needed. Keep at it, big Josh. Z